- Blog

#Azure #Blockchain

Starting a blockchain project

- 23/08/2021

Reading time 5 minutes

This is the second part of the blog series “Blockchains and Azure”. The first part was about Azure’s blockchain offering and can be found here.

The aim of this blog post is to explain what blockchains are and what kind of food they ingest. The fundamentals of blockchains are, by nature, rather technical, so parts of this post will require some technical background. But fear not, I’ll try to make the ride as smooth as possible. I will omit some details, and may even misguide a little bit in order to keep this post concise.

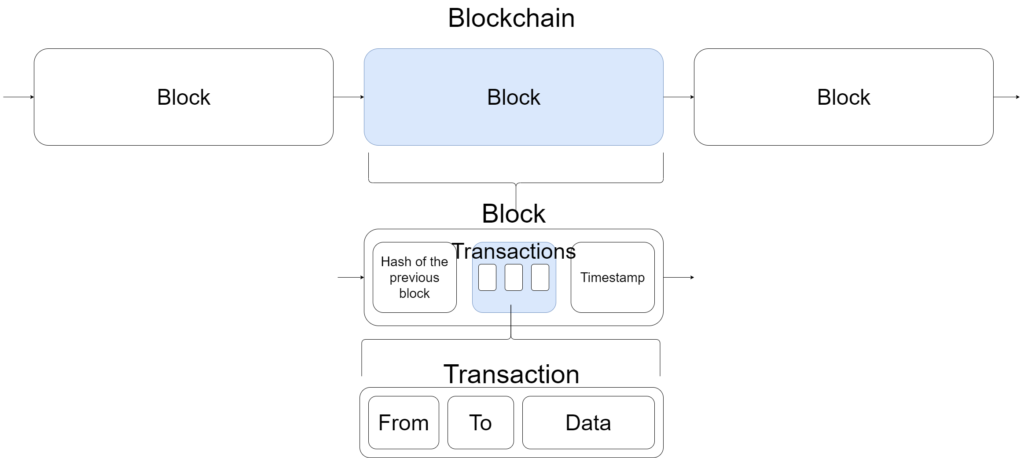

As the name suggests, a blockchain is a chain of blocks. When new data enters the blockchain, new blocks are formed and they join the chain of previous blocks. The chain can not be broken, and there is always exactly one block after any given block.

A block contains three main pieces of information:

Furthermore, a transaction contains three main pieces of information:

Any change in the block’s data results in a different block hash. Therefore there is no way to change data inside a block afterward since it would render the block hashes of all subsequent blocks invalid. That’s why blockchains are said to be immutable. Furthermore, blockchains are typically transparent, since everyone can read data in the blocks.

You can consider a blockchain as a distributed ledger where multiple parties can read and write at the same time.

So, we have a blockchain. Great. But what do we need if we want to send information into it?

You, as the sender, need a blockchain wallet. This is basically a private/public key pair, which you can create online or offline. You use the private key to sign information, and the public key is used to form your public address inside the blockchain. So private key results deterministically in a public address.

Whenever someone wants to send something into a blockchain they create a transaction. A transaction can be thought of as an envelope for all the needed information. The transaction has to state who is the receiver of the transaction (a public address) along with the desired payload data. Once a user signs the transaction with his private key, he becomes the transaction’s sender.

Once you have your transaction all ready and signed, you can send it to a node that relays it to all of the other nodes in the blockchain. Eventually, some node picks it up and includes it in his own block. Once the block is ready (each block can only fit in a certain amount of transactions), the node broadcasts the block to all of the other nodes, which include it in their view of the blockchain. Once most of the nodes have validated and included the block, the block (and subsequently all transactions inside it) is considered final, and more blocks can be built on top of it.

Then what about the blockchain itself, how is it formed? There isn’t much point in running a blockchain by yourself, so you need multiple (client) nodes that are interacting with each other to form a blockchain. A node is simply a program running on somebody’s computer. So, to interact with a blockchain, you need access to a node that participates in forming the blockchain.

Since a blockchain consists of its nodes, there is no single point of failure. Depending on the blockchain type, all nodes are either equal or, at least, highly redundant.

Now I hear you asking, how on earth are medieval knights related to blockchains? Well, that is an excellent question!

There are a few problems with the aforementioned logic of creating blocks. These problems are:

All of these problems are covered by what is called the “Byzantine Generals Problem”. It’s a fictitious story in which disconnected Byzantine armies try to reach a consensus (an agreement) on when to attack an enemy.

To solve the aforementioned problems, we set a requirement for broadcasting new blocks: the broadcaster needs to do some work before a block is considered valid. Also, the network has to be able to trust that more than half of its nodes are honest (doing their work correctly). Unfortunately (and fortunately) I’m not going to go through the solution in detail, but you can read it for example here. Spoiler: the solution includes concepts such as “Proof of Work” and “mining”.

So, in essence, blockchains solve a generic (or should I say, general) problem with information correctness in decentralized networks.

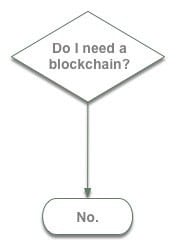

A cautious yes.

Blockchains, especially the publicly available ones, are good for environments, where the participants don’t trust each other. Or, hmm, no. To make this a bit more clear: they are good for environments, where the participants don’t need to trust each other. As long as the participants trust the underlying blockchain technology, they can be sure that no participant can abuse the system, by for example falsifying records.

You can also consider blockchains as highly accessible databases which have the ability to reach eventual consensus with an arbitrary amount of readers and writers.

Since public blockchains have no trust requirements, some blockchain types are getting widely popular in decentralized financing. Many blockchain types include their internal cryptocurrency, which can be sent along with transactions (yes, Bitcoin is one of them). During the last year or two, this had lead to enormous growth in various decentralized finance platforms. That is a bit of an in-depth topic, but I’m hoping to cover also that in some later blog posts since that is very close to my heart. Just as a teaser, you can peek at current charts about decentralized finance here.

My next blog post will probably be about the different blockchain types and their uses. Maybe I’ll even have a poke at how Zure could use blockchains with its clients. Let’s see!

No knights were harmed in the writing of this post.

Our newsletters contain stuff our crew is interested in: the articles we read, Azure news, Zure job opportunities, and so forth.

Please let us know what kind of content you are most interested about. Thank you!